Do you think of college as a right or a privilege?

Your answer will shape how you perceive the role and place of higher education in American society today. How much should college cost, for example? Who should have access? What role should the government play?

More importantly, your answer may depend on what you think college is for. As Peter pointed out in a recent column, many these days see college as an investment opportunity, a large down payment on a good job that had better produce solid returns. College is about careers—high paying, powerful careers, to be precise.

If that is the case, one straightforward but perhaps limited measurement of universities will concern how well they accomplish these objectives for the price. Raj Chetty and colleagues, for example, assess colleges by their relative effectiveness in moving someone from the bottom to the top quartile of the income distribution, with schools like City University of New York (CUNY) and UT Rio-Grand Valley rising to the top.

While this question is interesting and empirically tractable, it seems to undercut a broader possible sense of purpose. Let’s consider this question instead: Do you think a strong system of higher education is essential for a healthy society? A healthy democracy?

Broader Purposes

The founders of the nation thought education and a healthy society went hand in hand. Despite massive disagreements, political enemies found themselves concurring on the importance of education. An “informed citizenry,” they argued, was essential to a healthy republic. Thomas Jefferson believed that “the foundation for a working democratic republic had to be an educated electorate,” while his friend and enemy John Adams repeatedly urged education as essential to liberty.

Such views fueled the eventual rise of public universities and their spread across the nation. New states out west (now the Midwest) were pockmarked by tiny towns and public schools of higher education.

What the original founders imagined as “education,” however, may be a far cry from today’s circumstances. Colleges like Harvard were still reserved for gentlemen. Public grammar schools taught history, which was considered useful and necessary for citizenship, while private schools taught classics to train gentility. Social mobility was not part of the plan. These founders wanted all people to be educated—and all to know their place.

Even so, I wonder how much questions of citizenship, democracy, and social good surface in discussions about the purposes and outcomes of college. Such concerns have historically been a larger part of the picture. In “Live and Learn” from 2011, for example, Louis Menand helpfully articulated three common visions of higher education’s purpose:

1. Meritocratic: College is all about the grade, the selectivity, the sorting out of talent through hard work, discovering who rises and rewarding them accordingly.

2. Democratic: College is about the content, access to common materials across society, civic lessons and ideas useful for the life and strength of society.

3. Vocational: College is all about the job.

Other purposes might be added. But how we imagine the purpose of college today (and perhaps the loss of imagining its larger role in society), seems to owe a great deal to debt.

The Pedagogy of Debt

In my first year at WashU, I met with a young student who loved literature and history. The subjects fascinated her. She wanted to major in one, but she faced a real problem: if she did, her parents would not pay for college. What should she do?

Money matters. And leaving school with no loans makes a huge difference. I wished for this student to pursue her passions, but I advised her to appease her parents.

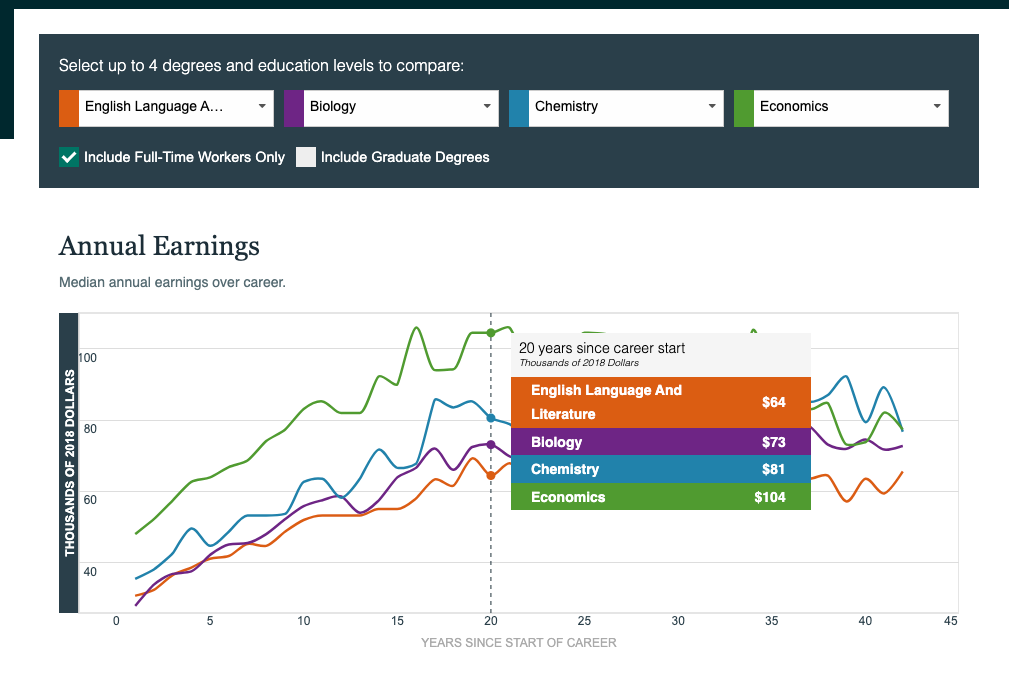

Appeasing them, however, could still entail aligning on a few shared facts, many underappreciated by the “consumer” of higher ed. First, while the choice of a major can make a difference to income, what matters most is a graduate degree. That just makes sense. An English major who goes to law school will likely earn more than a bio major who never gets another degree. Stopping at the bachelor’s, according to some charts, means those who major in the humanities actually make a slightly higher income than those who major in life sciences.

On other charts, English hangs close to biology, but earns less than business, economics, or chemistry. Still the earnings potential may not be as dramatic as some assume. It varies over time. Life as lived seldom turns on a college major, and a great deal depends on whether graduate school ensues.

For all the facts and stats gathered, for all that the story has been told in major outlets, my student’s parents, like most parents, were not persuaded. The student shifted to business, though eventually, I heard, she added a history major as well.

But again, while potential income remains an important question, in what ways was our discussion flattened by looking early and only at economic returns?

In an extraordinary piece on “The Pedagogy of Debt” (unfortunately paywalled!), Jeffrey Williams lays out the larger story of what my student experienced. Debt shapes majors, sure. But more importantly, debt teaches society to view college in a certain way. It focused our attention on the vocational and credentialing parts of education, but perhaps at the expense of the democratic. The higher the debt, the more apt we are to believe higher education exists just to pay it off. I might educate my students, but debt educates their parents.

I knew this lesson myself. In my senior year of high school, I applied to two colleges: Calvin and Princeton. Why two? Money, primarily. Calvin, I knew, would be free. Even if I got into Princeton (I didn’t), I doubted that it would be worth the cost. Calvin was a good school. It offered a broad and confident engagement with the world. It excelled in the humanities. And every year, it sent a large number of graduates into great PhD programs. Why pay for college when I could have all that for free?

Cost mattered to me clearly, and it constrained what colleges I even considered. But it also liberated me. With no student loans, I did not have to think about how to pay them back. I did not consider income when I considered a career. I took a part time job after college and worked on a novel in coffee shops all over Grand Rapids. Why not? I always wanted to try it. And I could.

Romance and the Bill

By disposition and experience, I tend to have a romantic notion of college. Here is the place to gather a broad, new knowledge of the world. Here is a space set aside to think with thinkers across thousands of years. Here is a world unto itself—a universe at the university—to get perspective on what the world is all about before launching into it.

Yet for all my romantic notions, I realize that debt often holds sway. My own pedagogical attempts run up against the pedagogy of debt.

Is higher education a privilege or a right? Is it about personal gain or communal good? Does it serve democracy? Does it have a social purpose? Does it liberate students to pursue their passions, including lives of service to others, or does it constrain them to careers that promise certain outcomes?

How we answer such questions may depend a good deal on how much college costs.

Perfect timing on this piece, Abram! My Argumentation class takes up the theme of higher education's purpose, a theme we're really going to be leaning into this semester.

I'm always dismayed to discover just how much my students' sense of the purpose of college departs from my own--and, frankly, sometimes in ways that downright depress me. And they're always quick to remind me, in turn, that my sense of college's purpose has much to do with my own various privileges.

I wonder what other potential purposes you might add to Menand's list. The "democratic" rubric captures quite a lot, but doesn't quite capture a category I might call "humanistic" or something similar. In other words, I think "democratic" too strongly signals citizenship and nationhood. Perhaps I'm being too narrow, but I think there's a broader set of abstract goals that goes unnamed here. I'll definitely be taking a look at the Menand piece.

Great post, Abram. As we discussed beforehand, I think one question is how to think about debt more broadly. In running experiential learning with clients, I sometimes find that when it is "free" they have less skin in the game than if it were paid. This is note a case for debt, in and of itself, but does raise the question of how paying for something (or paying more for something) increases the value we might get out of it. Here is a piece on research showing that paying even a nominal amount for something increase the value we get out of it... looking at mosquito nets, as one example: https://www.economist.com/international/2008/01/31/net-benefits.