Navigating Fractures of Class

Reflections on class from a few summer readings.

Harbor Springs, MI

July 2025

I have long wrestled with what kind of writing fits best in a newsletter versus other more “formal” medium -- a chapter, a journal article, a (hard to find time for, perhaps forever in the future) book. Probably spurred on by the cooler air of a few weeks in the upper Midwest, one point of clarity on that question has emerged. This space, unlike an essay or article, is where less fully formed thoughts belong. This space isn’t for polished arguments. It’s for thoughts still taking shape. Less thesis, more conversation. The kind of ideas you’d share with a friend over dinner. And don’t we all need more of that in our lives?

What also struck me is how much these reflections are shaped by where and when they’re written. Time and place leave their imprint on thought. That insight came into sharper focus as I revisited the author and friend Jeff Chu’s regular newsletter. Each of his entries, like this one noted at the top as coming from summer in Harbor Springs, is grounded, dated, and located in a particular place and time.

And this context matters. My reflections while away from the day-to-day will be distinct from thoughts that emerge as the semester winds up next month. What comes to mind here is different than my meanderings while traveling in Hong Kong later this fall. Place and time matter.

This is why I always liked the idea of a commonplace book. Marcus Aurelius used such tools to gather quotations and chronicle observations relevant to personal development. Seneca used the same concept to collect illustrative examples stumbled upon over the course of a day.

In many ways, this kind of public commonplace book is what I (we) hope to achieve here. The broad topic of this newsletter -- what it means to live a rich life -- is not one I have a clear thesis to which I am trying to convert you. But, I deeply believe in the importance of the question and what progress can be made by exploring it in conversation with you all. Perhaps some of these ideas will find their way into that future aspirational writing project; if not, I can only hope they will take form around a dinner table in your home, and thus shaping something just as meaningful.

Specific to this piece, a newsletter from Harbor Springs sings of summer rhythms. While each summer inevitably takes a unique form, one rhythm that has remained constant for for my immediate family has been a vacation with siblings and our parents.

But rhythms inevitably evolve over time. The unique rootedess of a letter from Michigan in 2025 is different than it would have been in 2015. Over the past decade, as one example, the attendees have changed. My siblings and I have each built lives with spouses and then eventually kids added to clan. This year, my dad's health prevented him from coming with the rest of us, a new and sobering shift to our routine.

Perhaps it is the intimate connection of this season to family that inevitably draws me to novels and books about family during the summer heat. In past years, this has included works by Jonathan Franzen and Marilyn Robinson. This year, my book of choice was John Seabrook's The Spinish King. Focusing on the family lore of the beloved New Yorker author, the book is a Succession-like exposé of the family history behind the frozen vegetable empire, Seabrook Farms, an organization whose patriarch was once called the Henry Ford of agriculture.

There is wisdom in learning from the functions and dysfunctions of other family systems. While my family has its own quirks, I was comforted by the relative ease of our life relative to that of the Seabrooks. Take parenting, for example. It is hard not to hear the cautionary tales as John reflects on his relationship with father. He writes:

I was grateful to my father for my excellent education, as well as for supporting my early literary efforts and life in New York. But we weren’t particularly close. I found it hard to be myself around him. We played father and son as though we were acting our parts in a Restoration comedy.

Still another generation above, John’s father had his own version of a parental rift, one shaped by the family’s rapid climb through very different social classes. It is a story I see regularly in my work with entrepreneurs and family business owners. These individuals often rise from modest beginnings, building successful businesses that give their children lives vastly different from their own.

But if that initial distance also seeded disdain for the class above, such early formation can prove difficult to shake. Here again is Seabrook on that complex relationship:

At least some of the later conflicts between my father and his father can be attributed to their belonging to different social strata. Maybe the Seabrooks came up too quickly from the lower level of the social hierarchy, and their dizzying ascent triggered a psychic case of the bends, caused not by nitrogen bubbles in the blood but champagne bubbles at the dinner table.

Having never been good at sitting the moment, July also whispers of the end of summer and advent of the upcoming academic calendar. As a college professor, I’m reminded that the futures my students are stepping into can be just as tangled with questions of class as the family dinner table dynamics of the Seabrooks.

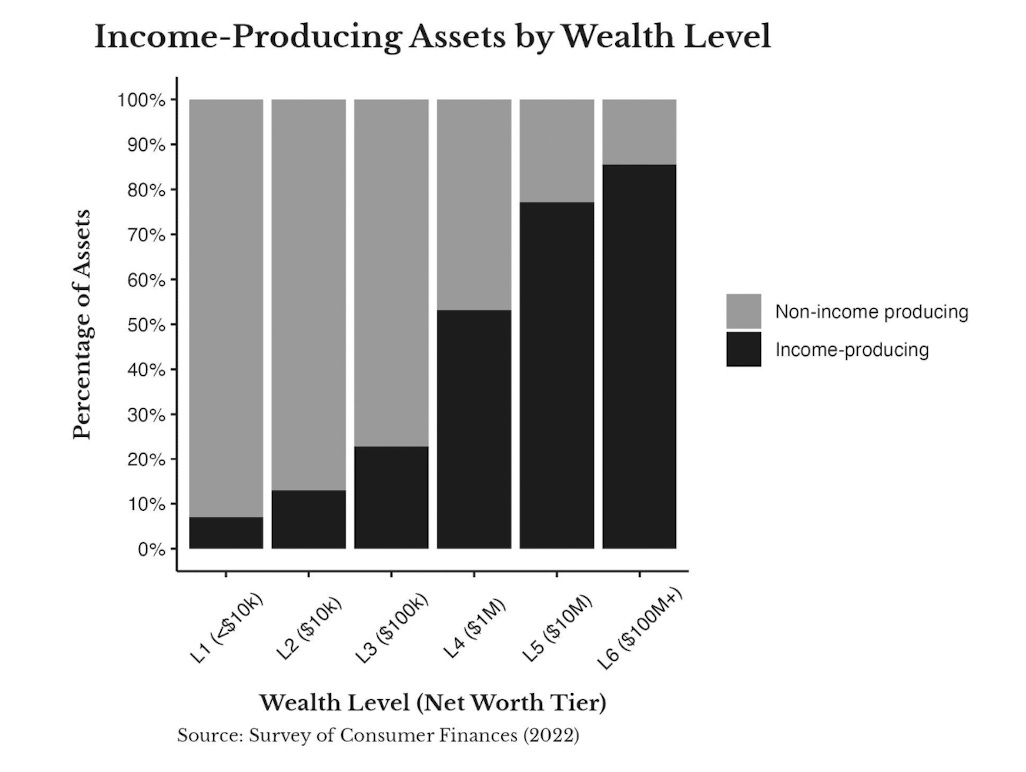

That thought was front of mind as I read reading Nick Maggiulli’s interesting new book, The Wealth Ladder. Drawing on some light assessment of the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, Nick’s book plots the different spending and saving behaviors of people of very different means. While a snoozer for some, I’m fascinated by how this data illuminates the underlying mechanics of class. Take, for example, the chart below on assets held at different wealth levels, divided between income-producing investments (stocks and bonds) and non-income-producing ones (like a car).

For Maggiulli, those differences became all the more personal when he stepped onto campus of one of the nation’s most elite higher education institutions:

I didn’t really start to understand money on a deeper level until I went to college. I was fortunate enough to get into Stanford University right as they rolled out a very generous financial aid policy. If your parents’ income was less than $100,000, you didn’t have to pay tuition, and if it was less than $60,000, you didn’t have to pay room and board. For four years I didn’t have to pay any tuition and for three of those four years I didn’t pay room and board either. I just happened to be at the right place at the right time....

There were also things related to class and etiquette. I’ll never forget the first time eating out with all my freshman hallmates at a restaurant. As the entrées started coming out, I noticed that no one was touching their food. Anytime I was with my family, I always started eating as soon as my food came because it would be hot. But as I discovered that night, eating before everyone else had their entrée was considered rude. So when my plate came, I didn’t do a thing. Then, as soon as the last entrée hit the table, it was as if a starting gun had been fired. Everyone started eating.

More relevant to those things that can drive class-mobility, Nick goes on to share his own ignorance around the importance of the sophomore year internship until running into a friend busy prepping for a set of big interviews. This moment ended up being a wake-up call, and one that got him to start acting in ways that aligned with his eventual professional path.

At the same time, exposure to certain social circles can exert its own pressure, gradually narrowing a broad range of possible futures into a single, standardized vision of what “success” is supposed to mean.

This point is echoed by current Harvard student Zoe Yu in a recent Slate essay . My colleague and friend from the Provost office shared this earlier in the week as we collectively strategized on what might be done to shape an incoming cohort of ambitious but still (hopefully) wonderfully open WashU students.

Here are a few key excerpts from the article, highlighting the strong pull many students feel toward investment banking and consulting:

Even for those students, it's not hard to understand the appeal. Consulting, finance, and tech are often the arbiters of campus prestige. From the moment a freshman steps on campus, all signs point to the highly selective student organizations that command instant peer respect. One of these clubs, the Harvard Undergraduate Consulting Group, boasts a 10 percent acceptance rate. On LinkedIn, HUCG's "analysts" and "associates"--that's the club's terminology, created to mirror the structure at actual firms--point to a "rigorous application process." Membership becomes shorthand for everything that an Ivy League student has come to value: smarts, exclusivity, social currency. Tack on the trips to New York for recruiting events and the head-spinning direct deposits from summer internships, and suddenly muddling through the uncertainty of "finding yourself" seems like an absurd detour.

I was that student not too long ago, though for me it came in graduate school rather than undergrad. MBB, a meaningless acronym prior to business school, quickly became known (and valorized) as McKinsey, Bain, and Boston Consulting Group. For my 26 year old self looking to prove I had made it, a role in those firms or a tenure track position as an Ivy+ institution was a sign that I had arrived. It meant I was enough.

But Yu is right to see that such choices can also reflect individual’s outsourcing the hard work of finding meaning to other parties. At the very least, it can be the attempt to delay this process. Harvard Business School Professor Mihir Desai makes a similar point in his book, The Wisdom of Finance. Far too often, the ambitious can become addicted to optionality, judging choices as “good” simply because they keep other doors open. Yu captures this tension well as she reflects on both her classmates and her own pull toward the same pattern.

"It sort of feels like you can delay finding what it is you actually want to do for at least a couple more years," she said. At BCG, where employees can join affinity groups and athletics clubs that call back to college life, and mentors talk frequently about "exiting" the industry, the future feels indefinitely--and blissfully--on pause.

Blissfully on pause — wouldn’t that be nice?

It is still summer in Michigan, but the sunsets are starting to migrate earlier in the evening. Our annual family vacations remain on the calendar, but each of us is a touch older and the crew a bit different. There is a joy in moments where it feels like time is standing still, blissfully on pause as Yu describes. But perhaps there is greater wisdom in realizing the inevitably marching forward. Might we be more in the moment as we give up on the make-believe of a forever summer?

Reading. Watching. Listening. Reflecting

A few materials that have caught my attention as of late.

Time up north has made me realize I am often too plugged in. With that said, I love Austin Kleon’s recommendation of “airplane mode as a way of life” and am hoping to lean into it a bit as I return to normal life.

Thinking a lot about Derek Thompson’s piece on the problems of people becoming increasingly less connected, what he calls the “death of partying in the USA.” What do you think? How are your social patterns different than a decade ago?

I am so proud of my friend Ryan and his newly launched venture to address US poverty through technologies like AI. It will be great to what they can build!

In a world of higher education that has long relied on an essay to assess learning, I have been reflecting a lot on what comes after this tool. This piece by Hua Hsu in the New Yorker is a good place to start.

I love writing, but find it hard to carve aside time in an increasingly administrative and parental life. These lessons from Ryan Holiday were helpful for me in providing inspiration for reset rhythms as I head back into autumn.

I would love to hear what is on your mind as well! In the meantime, be well, wherever you might be!

Peter

Very cool to see that the new economic mobility initiative is being led by a St. Louisan!