Suppose someone offered you a job for eight years. At the end of those eight years, you could retire rich.

Here’s the catch: for eight years, you will work endlessly. No vacations, no day off, only an occasional break, no skipping work for any friend or function. An average workday will be 14 hours. Most weeks, you will work seven days and top 90 hours.

Would you do it?

That question came up when we read Ayad Akhtar’s marvelous 2016 play Junk in “Markets and Morality,” a class Peter and I teach together. Akhtar dramatizes the story of Michael Milken, who launched the craze for junk bonds in the 1980s, went to jail, and now leads the life of a billionaire philanthropist.

When we posed this thought experiment to a room full of first-year students, about 40% took the deal. The rest refused.

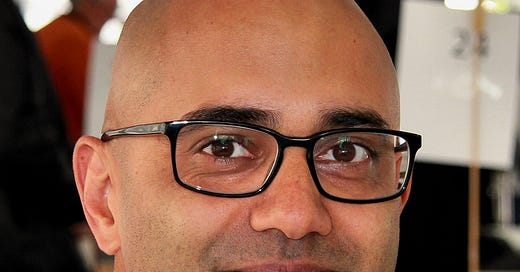

Playwright Ayad Akhtar at the 2012 Texas Book Festival

Larry D. Moore, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons.

At Stake

The thought experiment cuts at more than Milken’s own ethical conundrums (of which there are many). It hits at purpose, fulfillment, and the measurement of days.

Consider this: Eight years of your life constitutes 416 weeks out of the roughly 4000 weeks you have been granted on this earth. More than ten percent of your life. Is that worth the wealth?

Consider as well when that ten percent of your life would take place. As Peter and I posed this thought experiment to 75 teenagers, we were acutely aware of context. We are in our forties; they were all 18. Of the 40% who took the deal, many said they would never take it at our (old) age. Would you take the deal at 18? What if you were married and 30? How about at 40 with kids?

Each factor that might change your mind is a function of your priorities. And each priority points at your own sense of fulfillment—your vision (articulated or not) of a good life.

Money and the Good Life

Most people like making money, but does making more money lead to a happier life? Studies suggest a correlation between rising wealth and rising happiness, but after $75,000 or $100,000 the data get murky. Some scholars suggest a flattening, and indicate that other factors matter far more. More recent work highlights a continued rise of what they call “experienced well being” long beyond the initial threshold.

So how much money is enough for you?

In our thought experiment, I stated no particular amount. I just said that you would “retire rich.” Is there a number you had in mind? Is there a number that would sway you?

In Junk, the Milken character, named Bob Merkin, can never set a limit. His associate, Israel Peterman, starts floating crazy numbers, higher and higher, all the way to $250 billion.

Merkin says, “I don’t even know if that’s the number.” “For what?” Peterman asks. “To feel—I don’t know. Like it’s…enough,” Merkin says. After more back-and-forth, Peterman offers his father’s advice:

“When you don’t define your own limit, the limit comes to find you.”

Where do you put “enough,” and why? And would you be able to accept that limit if it came?

When I was a graduate student, I couldn’t imagine making more than $100,000 per year. It was an inconceivable amount. If I ever made more than $100,000, I pledged to give all the rest away. Now I have three kids, tuition expenses, two cars, a mortgage, and a house that I’ve just been told needs tuckpointing.

“Tuckpointing” is a word I had never heard before as a grad student.

Apart from rising expenses and expectations, work habits produce habits of work. Eight years can shape you to keep going for more. Suppose even greater wealth could be had for just four more years. And why not gain more with two more years beyond that? When does it stop?

“When you don’t define your own limit, the limit comes to find you.”

Work and Purpose

Money is not the only concern, however. In our thought experiment, I have not explained what kind of work the eight years would entail. How much does that matter?

Plenty of people, after all, already labor extraordinary hours for significant periods of their life to achieve an outcome clearly seen. In 2021, a set of junior bankers at Goldman Sachs put out an anonymous report on the impact of their 18 hour days on life satisfaction. Medical residents routinely work 80-hour weeks with 24-hour shifts—and that is after regulations imposed new limits in 2017.

But it isn’t just medicine or finance. And a greater income is not always the outcome.

In a recent NPR story, for example, Burnell Cotlon talked about laboring 14 and 15 hours each day to open the only grocery store that now exists in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans. Hurricane Katrina had devastated the neighborhood. No grocery stores remained. People had to take three buses to buy a loaf of bread.

“I was taught if there's a problem,” Cotlon said, “somebody got to make a move.”

At the end of the story, Cotlon’s mother asks him to reflect on his legacy. This is how Cotlon responds: “You know how people say you only live once? That's not the truth. You don't just live once. You only die once. You live every day. So every day that you live, you have to do something impactful. You're not just born to fall in love, have a few kids, get a job, pay your bills, grow old and die. That's not why you're here. You have to find out why you're here. And my purpose is easy. It's service.”

And serve he has: 14-hour days, 15-hour days. First a grocery store. Then an internet cafe so kids could do their homework. The long days growing longer, the needs interminable, the Ninth Ward coming back. It was never the money. It was the people he loved, the home he hoped to rebuild: “what motivated me the most was seeing the people that was walking by with the groceries and seeing them get off the bus with all of those bags,” Cotlon explains. “That made me work harder.”

Eight years ago that grocery store opened.

There are many ways to live a rich life. Only some of them involve riches.

Loved this podcast on “enough” being more of a well honed felt sense than an equation:

https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/we-can-do-hard-things-with-glennon-doyle/id1564530722?i=1000627034489

This resonated, especially this line: “When you don’t define your own limit, the limit comes to find you.” Oof.